The Oil and Gas industry in the insurance market is usually categorised between Onshore/Offshore or Upstream/Downstream. It includes a chain of businesses relating to extraction, transportation, refining, petrochemical and chemical – essentially from the carbon in the ground to the processed materials that are used in many manufacturing applications that we rely upon in our everyday lives.

In this technical briefing will explore this value chain, identifying some of the key distinctions and how this can impact the measurement of economic losses in this sector.

“Upstream” refers to exploration and production, including wells, platforms, and mobile drilling units. Where this happens determines whether it is classified as “Offshore” (e.g. the North Sea or the Gulf of Mexico) or “Onshore” (e.g. Ghawar Field in Saudi Arabia or Permian Field in Texas/ New Mexico). The well-stream may consist of crude oil, gas, condensates, water and various contaminants. Separation equipment can split the flow into the desired elements, removing water, sand and other unwanted components.

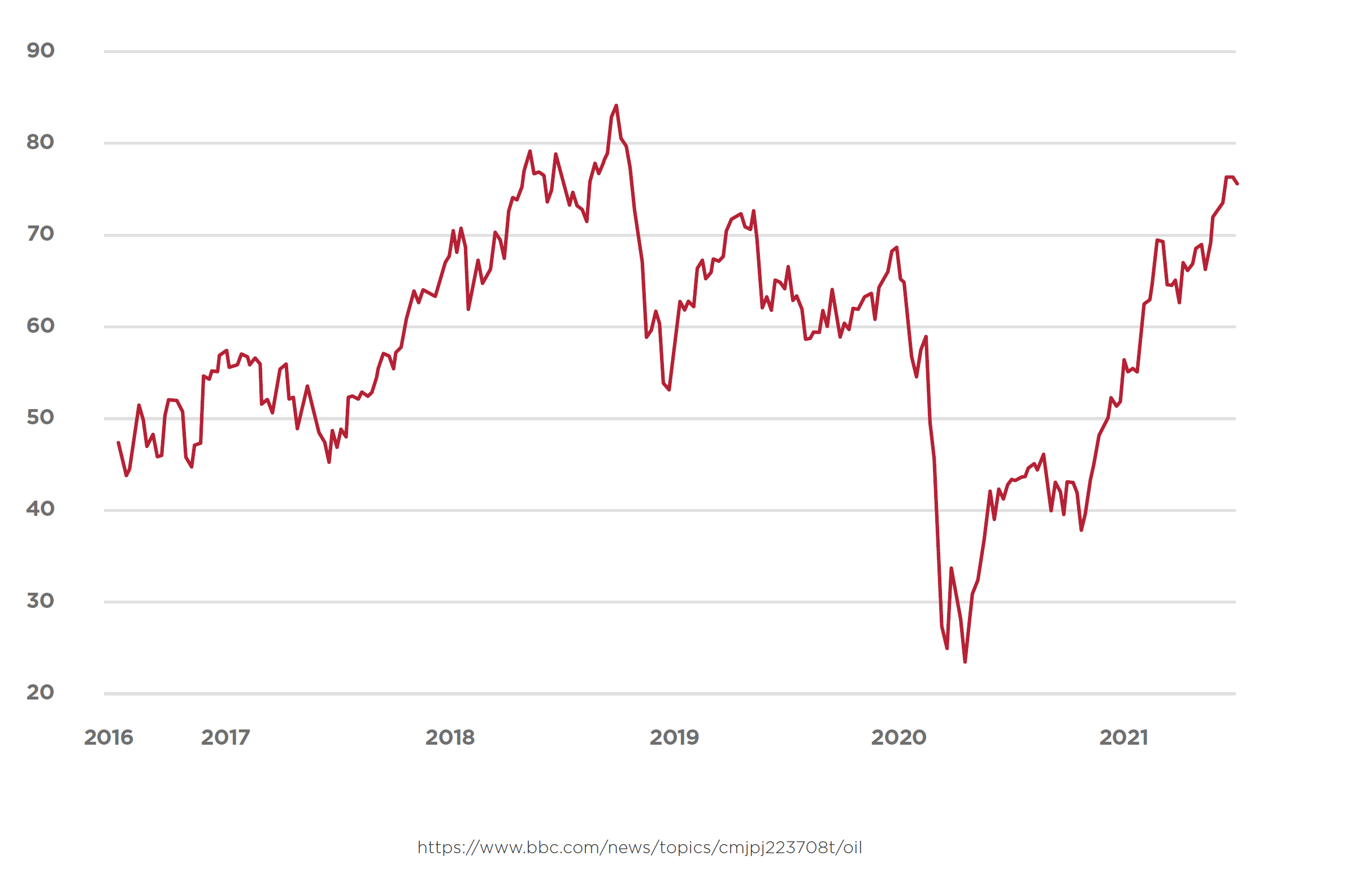

Often, upstream production facilities are insured on a loss of production income (“LOPI”) basis. Whilst the oil remains in the ground, these calculations are designed to protect the producer’s revenue stream. These policies do not provide a true indemnity, as the wording prescribes a fixed price per barrel (set at policy inception) multiplied by the expected production.

Example

A policy that commenced on 1 January 2020, set at USD 65 per barrel, would have over-indemnified the policyholder significantly during 2020 due to the significant drop in crude prices following the Covid-19 outbreak and a significant discounting of crude by Saudi Arabia. In contrast, the same policy commencing on 1 January 2021, set at USD 65 per barrel, would lead to an under-indemnification, since prices at the end of February 2021 had recovered to USD 77 per barrel (Brent Crude).

“Midstream” refers to any point in the oil and gas production process between upstream and downstream. Midstream activities include transportation of hydrocarbons (by pipelines and tanker vessels), storage and intermediate processing. When damage occurs to pipelines and other midstream infrastructure, this can give rise to contingent business interruption (“CBI”) claims, further downstream (or sometimes upstream), which can be challenging without the requisite cooperation from the third party, detailed contractual relationships or detailed trading records. Other midstream processing can include raw gas processing into different products or fractions. This can include removal of acid gases, water and other pollutants to produce:

1. Natural Gas – methane and light alkenes processed to a specified hydrocarbon composition;

2. Natural Gas Liquids (“NGL”) – purified ethane, propane, butane or a blended feedstock for a petrochemical plant;

3. Liquefied Petroleum Gas (“LPG”) – propane or butane blended and compressed to liquid at room temperature;

4. Liquefied Natural Gas (“LNG”) – refrigerated and liquefied for storage and transport;

5. Compressed Natural Gas (“CNG”) – methane compressed for storage and transportation.

These marketable products are then sold by contract at a certain specification which will typically outline content, volume, density, calorific value and suchlike, which may vary by operator or distributor.

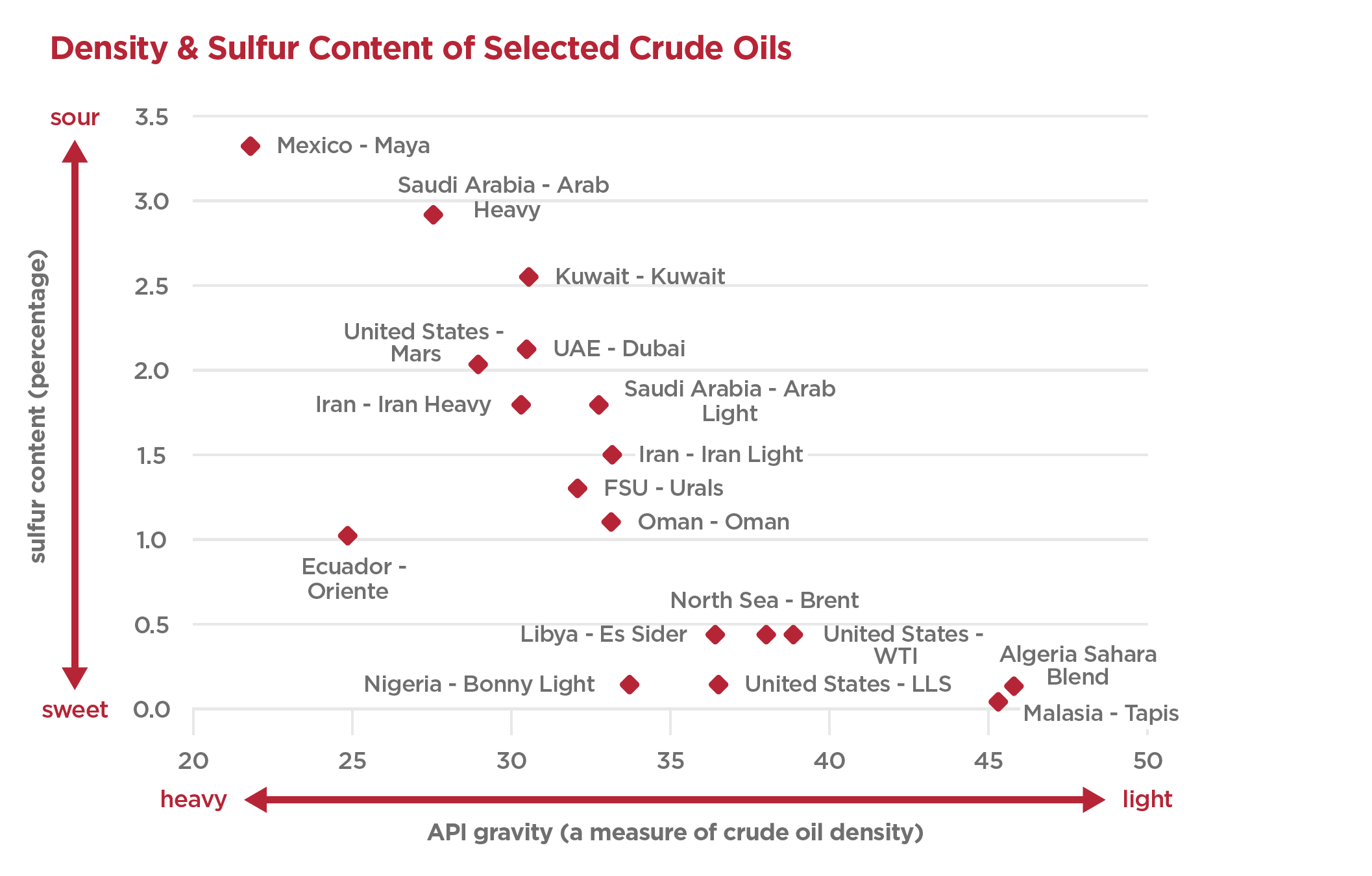

Likewise, Crude oil can vary, depending on the density (“Heavy” or “Light”), categorised based on the American Petroleum Institute (“API”) gravity scale, and the classification of “sweet” or “sour” (a measure of sulfur content) of the crude.

“Downstream” refers to the refineries, LPG and Petrochemical plants that convert the gas or crude into separate products. The mix of different crude grades that the refinery is running is referred to as the “crude slate” and may change over time, depending on market conditions (including availability and pricing). The refinery will optimise the crude slate to maximise profitability. Therefore it is important to consider the conditions at the time of any loss, as the historic results may not necessarily be reflective.

Simple refineries use fractionation/distillation to produce a wide variety of different products from every barrel of crude oil processed. Usually, the aim is to produce as much “light” product (gasoline, jet fuel, and diesel as these are often of highest value) with the other products being essentially by-products of the process. Complex refineries take the heavier / longer chain hydrocarbons of lower value and “crack” them to produce lighter hydrocarbons, thus maximising profitability.

Major products from a refinery include:

- Propane – Feedstock for ethylene cracking / blended into LPG for fuel

- Butane – Feedstock for ethylene cracking / blended into LPG for fuel

- Naphtha – Feedstock for ethylene cracking

- Gasoline

- Aviation / Jet Fuel

- Kerosene – for domestic cooking, heating, and lighting

- Diesel – fuel for trucks, trains and heavy industrial equipment

- Bunker oil – fuel for power generation / large vessels

- Lube oil / grease for industrial use

- White oil – clear, odourless liquid used in the pharmaceuticals industry

- Bitumen / Asphalt – used for roads and manufacture of building materials

Following a loss at a refinery (particularly partial loss, which only affects a single unit), it is important to understand how throughput and product slate can be modified to mitigate the margin loss, depending on other plant constraints and contractual obligations. Detailed analysis of linear programming (“LP”) models and mass/material balances can assist with this exercise, often in conjunction with other experts.

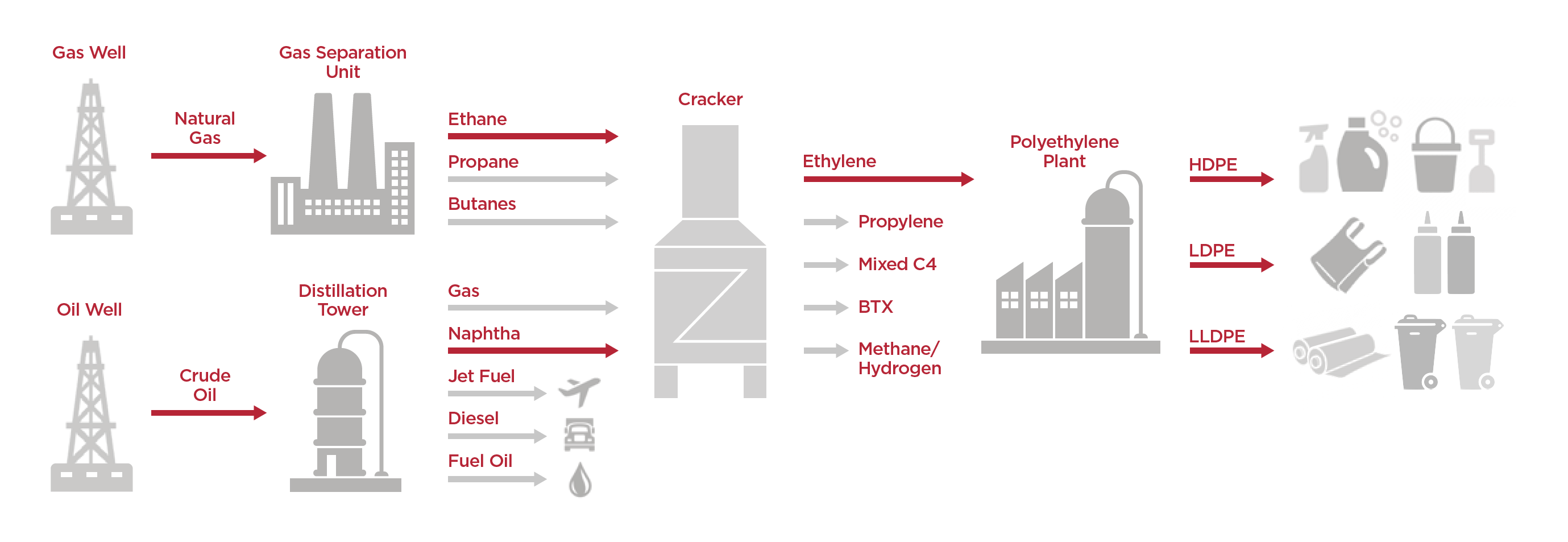

Further downstream of refineries and gas separation plants sit Petrochemical plants containing various plants, including Alkenes or Olefins plants such as ethylene, propylene and butadiene, which are ultimately used in the manufacture of plastics, rubbers and styrenes. Key features of losses in these areas include leading and lagging of market pricing, which can cause the margin per tonne to vary significantly, requiring a detailed study of market pricing for both end-products and key input feedstocks.

Having run through the value chain from extraction to petrochemical plants, we have set out below an example of the chain from carbon in the ground to finished products in the ethylene stream. Ethylene can be cracked from ethane (from a gas separation plant) or naphtha (from a refinery). Ethylene can then be processed into many other products such as polyethylene of different grades, which we rely upon heavily in our everyday lives.

We hope you have enjoyed this high-level tour through the oil and gas value chain. In subsequent case studies and technical briefings, we will explore some of these areas in more detail. In the meantime, if you would like to discuss any of these concepts or have an ongoing claim involving some of these components, please do not hesitate to reach out to one of MDD’s global energy team or your local contacts.

The statements or comments contained within this article are based on the author’s own knowledge and experience and do not necessarily represent those of the firm, other partners, our clients, or other business partners.